Failing to Train DeBERTa to Detect Patent Antecedent Basis Errors

Patent claims have a simple rule: introduce "a thing" before referring to "the thing." I figured a neural network could learn to catch when drafters mess this up. It did—90% F1 on my synthetic test data. Then I ran it on real USPTO examiner rejections and watched that number collapse to 14.5% F1. That's 8% recall. The model catches 8 out of 100 real errors. It's useless. At least I know why. Part 2 coming.

The problem

Antecedent basis errors are one of the most common reasons for 112(b) rejections. They're also one of the most annoying—purely mechanical mistakes that slip through because patent claims get long, dependencies get tangled, and things get edited over time. You introduce "a sensor" in claim 1, then three claims later you write "the detector" meaning the same thing. Or you delete a clause during revision and forget that it was the antecedent for something downstream.

"A device comprising a processor, wherein the controller manages memory." ↑ "the controller" appears out of nowhere—no antecedent

More examples of antecedent basis errors

Ambiguous reference

✗ "a first lever and a second lever... the lever is connected to..."

✓ "a first lever and a second lever... the first lever is connected to..."

When multiple elements share a name, "the lever" is ambiguous.

Inconsistent descriptors

✗ "a lever... the aluminum lever"

✓ "an aluminum lever... the aluminum lever"

Adding a descriptor that wasn't in the antecedent creates uncertainty.

Compound terms

✗ "a video display unit... the display"

✓ "a video display unit... the video display unit"

Can't reference part of a compound term alone without introducing it separately.

Implicit synonyms

✗ "a sensor... the detector"

✓ "a sensor... the sensor"

Even if they mean the same thing, different words require separate antecedents.

Gray area: Morphological changes

? "a controlled stream of fluid... the controlled fluid"

Often acceptable because the scope is "reasonably ascertainable," but some examiners may still flag it.

Not an error: Inherent properties

✓ "a sphere... the outer surface of said sphere"

You don't need to explicitly introduce inherent components. A sphere obviously has an outer surface.

When the USPTO catches it, you get an office action. You pay your attorney to draft a response. The application gets delayed. All for an error so mechanical, so tedious, that checking for it yourself feels almost insulting.

What's out there

Checking for antecedent basis errors feels like exactly this kind of task. So before building anything, I wanted to see what already exists. Turns out there are a few options—commercial tools, open source projects, and academic research—but none of them really solve the problem.

Commercial tools

ClaimMaster is a Microsoft Word plugin that patent attorneys actually use. It parses your claims and highlights potential antecedent basis issues—missing antecedents, ambiguous terms, singular/plural mismatches. They describe it as using "natural-language processing technologies" but don't go into detail. They've recently added LLM integration for drafting and analysis, though it's unclear if that extends to antecedent basis checking. No published accuracy numbers.

Patent Bots is a web-based alternative that claims to use "machine learning" for proofreading. They highlight terms in green (has antecedent), yellow (warning), or red (missing antecedent). But again, no published accuracy metrics. The marketing says "state-of-the-art machine learning" without explaining what that actually means.

LexisNexis PatentOptimizer is the enterprise option—expensive, closed source, aimed at large firms. It checks for antecedent basis and specification support, but I couldn't find any independent evaluations of how well it actually works.

Open source

On GitHub, there's antecedent-check. Despite the name, it doesn't actually check for antecedent basis errors—it just parses claims into noun phrases using Apache OpenNLP. The logic to compare "a X" against "the X" was never implemented. Last updated in 2020, 5 commits, 1 star. An abandoned prototype.

There's also plint, a patent claim linter. But here's the catch: it requires you to manually mark up your claims with special syntax—curly braces for new elements, brackets for references. The author's README admits it's "fragile" and "overdue for a complete rewrite." If you have to manually annotate your claims, you might as well just proofread them yourself.

Research

The most serious attempt I found is the PEDANTIC dataset from Bosch Research. They built a dataset of 14,000 patent claims annotated with indefiniteness reasons, including antecedent basis errors. Then they tested various models on it—logistic regression baselines, and LLM agents using Qwen 2.5 (32B and 72B parameters).

Their task was binary classification—given a claim, predict whether it's indefinite or not. The LLMs they tested (Qwen 2.5 32B and 72B) failed to outperform logistic regression, with the best model achieving 60.3 AUROC. Antecedent basis was the most common error type, accounting for 36% of all rejections.

But their task is different from what I wanted to do. Classifying "this claim has an error somewhere" is one thing. Pinpointing exactly which words are wrong is harder—and more useful if you're actually trying to fix the claim.

So that's the landscape: commercial tools that don't publish accuracy, open source projects that are abandoned or require manual markup, and research showing that even large language models haven't cracked this. The problem is still open.

Ideas to automate

The first thing that comes to mind is regex or rule-based matching. Scan for every "the X" and check if "a X" appears earlier. For simple cases, this works fine. But patent language gets complicated fast. Consider "displaying a video on the screen" followed later by "the displayed video"—the root word changed form. Or "a video display unit" followed by "the display"—a compound term got shortened. You'd need morphological analysis, a dictionary of compound terms, and rules for every edge case. It gets brittle.

What about LLMs? The researchers behind the PEDANTIC dataset tested Qwen 2.5 (32B and 72B) on a related task. The results weren't great. When you need token-level precision—knowing exactly which words are the error—generative models struggle. They're optimized for fluent output, not surgical accuracy.

That left token classification. You feed the model a claim, and it labels each word: is this the start of an error, a continuation of one, or fine? This is exactly what BERT-style models were designed for. I went with DeBERTa-v3-base—it takes the parent claims as context, looks at the target claim, and marks what's wrong.

The training data problem

PEDANTIC has labeled antecedent basis errors, but only ~2,500 training examples. I wanted more data and control over the error types. So I decided to generate synthetic training data.

I started by pulling ~25,000 granted US patents (2019-2024) from Google Patents BigQuery. These are clean, examiner-approved claims with no antecedent basis errors—at least in theory. I parsed out the claim structure, built dependency chains so each dependent claim had its parent claims as context, and ended up with about 370,000 claim-context pairs.

Then I wrote a corruption generator to inject synthetic errors. The idea: take clean claims and break them in ways that create antecedent basis errors, recording exactly which character spans are wrong.

The six corruption types I generate

1. Remove antecedent

Find "a sensor" in context, delete it. Now "the sensor" in the claim is orphaned.

2. Swap determiner

Change "a controller" → "the controller" in the claim where no controller was introduced.

3. Inject orphan

Insert "the processor connected to" from a hardcoded list of 24 common patent nouns.

4. Plural mismatch

"a sensor" in context → "the sensors" in claim. Singular introduced, plural referenced.

5. Partial compound

"a temperature sensor" introduced → "the sensor" referenced. Can't drop the modifier.

6. Ordinal injection

"a first valve" and "a second valve" exist → inject "the third valve".

50/50 split between clean and corrupted examples. The corrupted ones got converted to BIO format (B-ERR for beginning of error span, I-ERR for inside, O for everything else) and fed to DeBERTa.

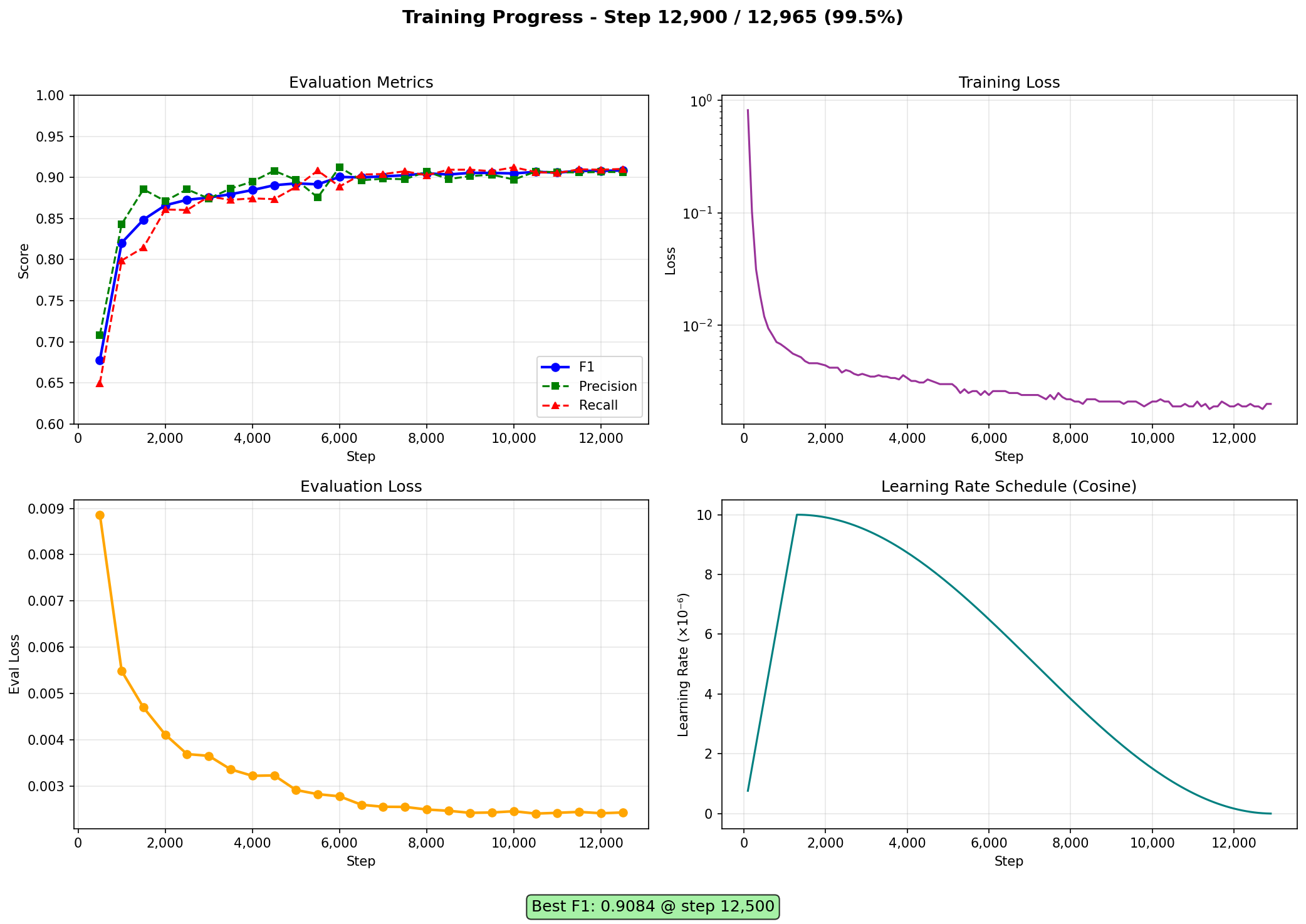

After about 12,500 steps, the model hit 90.84% F1 on my validation set. I was feeling pretty good about it.

Then I tested on real data

The PEDANTIC dataset contains actual USPTO examiner rejections with the error spans labeled by hand. This is the real thing—885 test samples where examiners flagged antecedent basis issues in actual patent applications.

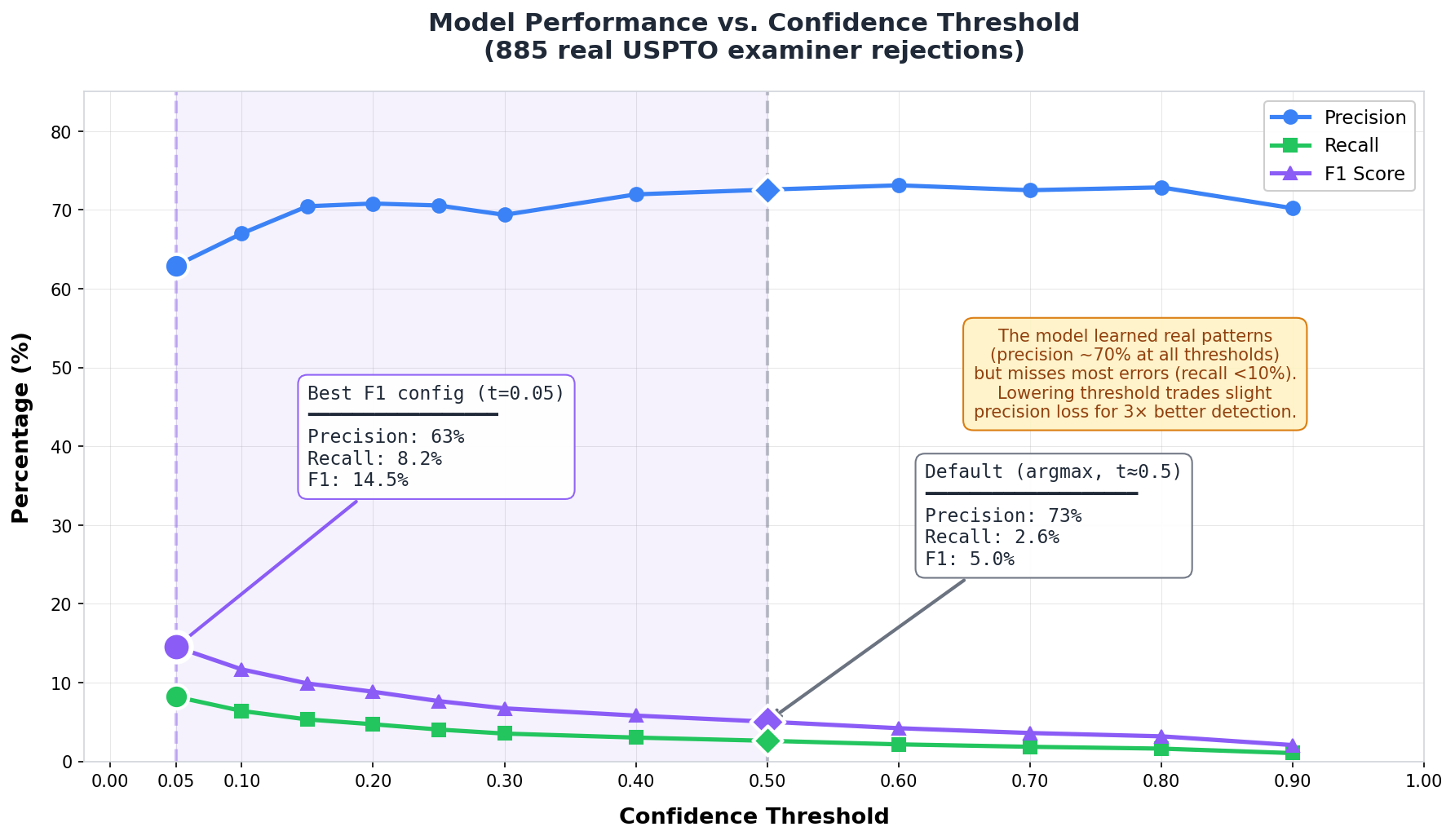

Out of the box, my model hit 5% F1. That 90% on synthetic data? Gone. But before giving up, I wanted to understand what was actually happening inside. The model outputs a confidence score for each token—how sure is it that this word is part of an error? By default, it only flags tokens where it's more than 50% confident. What if I lowered that bar?

Look at the blue line. Precision barely moves—stays around 70% no matter what threshold I pick. That's interesting. It means the model actually learned something real. When it speaks up, it's right about two-thirds of the time, whether I make it cautious or aggressive.

The green line is the problem. At the default threshold, recall is 2.6%—catching almost nothing. Crank the threshold down to 0.05, and recall triples to 8.2%. Still bad, but less bad. F1 goes from 5% to 14.5%. I'll take it.

So the model isn't broken. It learned patterns that transfer to real data—just not very many of them. The synthetic corruption I generated covers maybe 8% of what USPTO examiners actually flag. The other 92%? Patterns I didn't think to simulate.

Exploring the data

Before trying to fix anything, I wanted to understand what's actually in PEDANTIC and what my model sees. I ran every test sample through the model at threshold 0.05 and categorized every prediction.

What the model catches

Of the 258 true positives, 92% start with "the"—phrases like "the user", "the source profile", "the matrix". This makes sense. My synthetic training data generates errors by swapping "a X" to "the X", so the model learned to flag definite articles that lack antecedents. When it sees "the controller" and can't find "a controller" earlier in the context, it speaks up.

What it misses

The 2,883 false negatives tell a different story. Only 38% start with "the". The rest?

"widgets", "pattern", "text content" 37% of all errors. The noun is used without "the" or "a" but still lacks proper introduction.

"said widget", "said data" Patent-speak for "the". My model catches almost none of these despite 30% augmentation in training.

"a location of the occluded area" The error is "the occluded area" but PEDANTIC marks the whole phrase. Different annotation granularity.

"it" 20 cases. Never in my training data because I focused on noun phrases.

False positives

The 152 false positives are mostly patent boilerplate: "The method of claim 8", "The system", "The apparatus". These always have antecedents—"method" refers to the claim itself, "system" to whatever was introduced in claim 1. The model doesn't understand claim structure, just surface patterns.

Data quality

Some PEDANTIC annotations look like parsing artifacts. I found dozens of instances of "d widgets" and "idgets"—clearly broken spans from the word "widgets". A small percentage of false negatives have suspicious patterns: spans starting with spaces, single characters, or truncated words. Not a huge problem, but worth noting.

The gap

Now the picture comes together. Go back to those six corruption types I wrote—every single one produces errors starting with "the" or "said". That's all the model ever saw during training.

But real examiner rejections are messier. PEDANTIC breaks down like this:

| Pattern | % of PEDANTIC | Recall | Training |

|---|---|---|---|

| "the X" | 42.0% | 16.2% | trained |

| bare nouns | 37.3% | 1.0% | never |

| embedded "the" | 9.6% | 9.3% | never* |

| "a/an X" phrases | 6.2% | 1.0% | never |

| "said X" | 4.3% | 1.5% | 30% aug |

| pronouns | 0.6% | 0.0% | never |

* Embedded patterns get partial credit when our "the X" detection overlaps with the annotated span

But wait—if I trained on "the X" patterns, why is recall only 16%? Where did the other 84% go?

Digging into the 84%

I dug into the model's actual predictions and found bugs in my corruption logic.

Distribution mismatch on context. 51% of missed "the X" errors are in independent claims (no parent context). My training data has 18% without context—not zero, but the distribution is off. The model learned to rely heavily on cross-referencing "the X" against "a X" in context. When context is missing or sparse, it's less confident.

I trained on wrong labels. Here's the bug: 7% of my training errors are "The X of claim N" patterns—things like "The method of claim 1, wherein...". These should never be errors. The phrase "of claim 1" explicitly provides the antecedent. But my remove_antecedent corruption doesn't understand this. It sees "a method" in context, "the method" in the claim, removes "a method", and labels "The method" as orphaned. Wrong.

This created spurious patterns. 10.8% of error tokens in my training data appear within 3 tokens after the [SEP] separator—right at the claim start. The model learned "claim start → likely error". On real data, it puts ~0.3 probability on [SEP] and claim-start boilerplate. Actual errors also get ~0.3 probability. The model can't distinguish real errors from the noise I accidentally taught it.

Real errors are more subtle. My synthetic training creates obvious cases—I delete "a sensor" from context, making "the sensor" clearly orphaned. But 17% of PEDANTIC's "the X" errors have an "a X" that does exist somewhere earlier. The examiner flagged it anyway because the reference was ambiguous, or referred to something different, or had a scope issue. I never generated these nuanced cases.

The false positives

The 152 false positives are almost all patent boilerplate: "the method", "the apparatus", "the system". Now I know why—I literally trained the model to flag these. Those 7% wrong labels taught it that claim-start phrases are errors. The model is doing exactly what I trained it to do. I just trained it wrong.

The real gap

90% F1 on synthetic data, 14.5% on real data. The gap is my corruption logic. I accidentally trained the model on wrong labels, created spurious patterns around [SEP] and claim-starts, and never generated the subtle ambiguity cases that real examiners flag. The model architecture is fine. My training data was broken.

What's next

This is Part 1. The model architecture isn't the problem—DeBERTa learned exactly what I taught it. The corruption logic is what's broken. In Part 2, I'll try to fix it:

Fix the bugs. Filter out "The X of claim N" patterns from error labels. Add explicit negative examples where boilerplate phrases like "The method of claim 1" are labeled as NOT errors. Rebalance the context distribution to match PEDANTIC (more independent claims, fewer dependent).

Cover more patterns. 37% of real errors are bare nouns—"widgets", "pattern", "text content"—and I never generated any. Add corruptions that reference bare nouns without introduction. Generate "said X" errors more aggressively (30% augmentation wasn't enough for 1.5% recall). Add pronoun cases.

Generate harder cases. Right now I create obvious errors—delete "a sensor" and "the sensor" is clearly orphaned. But 17% of real errors have an antecedent that exists but is ambiguous, refers to something different, or has scope issues. This probably requires either manual curation or a smarter generation strategy that intentionally creates near-miss patterns.

Or I might skip synthetic generation entirely and fine-tune on PEDANTIC's training split. It's smaller (only ~2,500 antecedent basis examples vs my 185,000), but it's real data with real annotation patterns. The distribution would match by construction. We'll see.

January 2025